Reconstructing How We Deliver Electrical Safety Knowledge to Minimize Exposure and Help Save Lives

By: Corey Hannahs, Contributor

By: Corey Hannahs, Contributor

Electrical safety is without question a critical component to a successful electrical installation. Yet many seem to have differing viewpoints on what is safe and what risks should be taken. At the root of every electrical safety incident is a person who made a choice, based on the information they had available. Sometimes proper training is not provided and at other times, proper training may have been provided, but chosen not to be utilized by the individual. Either scenario can end in a fatal result, or a non-fatal physical or mental injury that continues to impact the victim for years to come. Even when the incident proves to be non-fatal, long-term sequalae, or lingering effects, from a previous electrical injury have been known to produce neurologic, psychological, and physical symptoms. With so much at stake, it is crucial that electrical safety training continue to be reevaluated by all involved to determine where we can improve.

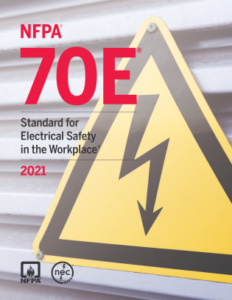

NFPA 70E

Having proper knowledge of how to perform electrical tasks safely is a necessary, solid foundation. NFPA 70E® Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace® should be the cornerstone that electrical safety training is built upon, as it provides guidelines and procedures for working safely around electricity. Something to consider is modifying how much training on electrical safety takes place. For example, looking at the apprenticeship model in my home state, there is a minimum of 576 hours of classroom-based related technical instruction (RTI) required. Of the 576 required hours of RTI, 450 hours are mandated to have so many hours trained on specific components. The safety component requirement is 10 hours of the 450. There is also no mandate that those 10 hours be electrical safety training such as NFPA 70E, as it could revolve around first aid, CPR, AED, OSHA training, etc. and still meet the requirement specifications. All things considered, an apprentice could go through an entire 576-hour program and receive only 10 hours – equating to 1.74% of the full program hours – of safety training that may or may not be electrical safety based. Sure, there are 126 hours additional flexible RTI hours of training available to train on electrical safety, after the 450 required hours, but there is no mandate that electrical safety is part of those additional hours. And my state is likely not unique to this arrangement of electrical apprenticeship hours, as many states utilize similar templates provided by governmental organizations, such as the United States Department of Labor, as a baseline to create their individual state Standards of Apprenticeship. The quantity of electrical safety training that is required should be revaluated to better align with how important being safe around electricity is for individuals. There has to be more emphasis placed on the need for safety training that is specific to working around electricity within apprenticeship programs. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Standard 1910 has specific rules to help keep individuals safe when working around electricity, like Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in Subpart I, that are often met by using procedures within NFPA 70E. But training on these rules are not always built into apprenticeship programs themselves. Where required, employers often look to outside resources to train on NFPA 70E procedures that will help meet OSHA requirements. Apprenticeship programs need to be designed so the applicable electrical safety training is built into their programs and employers can train additionally, as needed, for job-specific or industry-based tasks.

Having proper knowledge of how to perform electrical tasks safely is a necessary, solid foundation. NFPA 70E® Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace® should be the cornerstone that electrical safety training is built upon, as it provides guidelines and procedures for working safely around electricity. Something to consider is modifying how much training on electrical safety takes place. For example, looking at the apprenticeship model in my home state, there is a minimum of 576 hours of classroom-based related technical instruction (RTI) required. Of the 576 required hours of RTI, 450 hours are mandated to have so many hours trained on specific components. The safety component requirement is 10 hours of the 450. There is also no mandate that those 10 hours be electrical safety training such as NFPA 70E, as it could revolve around first aid, CPR, AED, OSHA training, etc. and still meet the requirement specifications. All things considered, an apprentice could go through an entire 576-hour program and receive only 10 hours – equating to 1.74% of the full program hours – of safety training that may or may not be electrical safety based. Sure, there are 126 hours additional flexible RTI hours of training available to train on electrical safety, after the 450 required hours, but there is no mandate that electrical safety is part of those additional hours. And my state is likely not unique to this arrangement of electrical apprenticeship hours, as many states utilize similar templates provided by governmental organizations, such as the United States Department of Labor, as a baseline to create their individual state Standards of Apprenticeship. The quantity of electrical safety training that is required should be revaluated to better align with how important being safe around electricity is for individuals. There has to be more emphasis placed on the need for safety training that is specific to working around electricity within apprenticeship programs. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Standard 1910 has specific rules to help keep individuals safe when working around electricity, like Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in Subpart I, that are often met by using procedures within NFPA 70E. But training on these rules are not always built into apprenticeship programs themselves. Where required, employers often look to outside resources to train on NFPA 70E procedures that will help meet OSHA requirements. Apprenticeship programs need to be designed so the applicable electrical safety training is built into their programs and employers can train additionally, as needed, for job-specific or industry-based tasks.

Another item to consider is the methods by which electrical safety training is delivered. In the aforementioned apprenticeship program example, safety training is one of many training components within the program. But electrical safety is a critical part of many of the processes and procedures that are learned in other areas of an apprenticeship. How can a defective circuit breaker be changed out safely if electrical safety procedures aren’t followed as part of the process? Teaching electrical safety as part of the specific task process, instead of as a stand-alone component, would allow apprentices to learn safety as a step that is already built into the task. Just as it is learned that you turn a screwdriver to the left to loosen a screw that holds a circuit breaker in place, it could also be learned that establishing an electrically safe work condition (ESWC) is an integral step in safely changing out a defective circuit breaker. Understanding electrical safety is part of the process but building it into specific tasks will help individuals understand electrical safety needs and form habits helping to ensure they return home safely each night. As constructors, methods are constantly revaluated to build things that are more viable and sustainable, always trying to determine how to “build a better mousetrap.” If there is a better way to reconstruct the delivery of electrical safety training, versus the way it has always been done, it only makes sense to move forward doing so. Safety needs to be trained as a step built into the task-specific process and not treated as an add on component.

Electrical safety is ever evolving and no one person holds all the answers. It becomes necessary to look at and evaluate what becomes the norm, eliminate any complacency, and be open to rethinking how we train electrical safety. College football coach Bo Schembechler was known for saying, “Every day you either get better or you get worse. You never stay the same.” When it comes to electrical safety, I believe that also holds true. We must continue to use every new day as an opportunity to get better on how we train electrical safety. Lives depend on it. ESW

Corey Hannahs is a Senior Electrical Content Specialist at the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). In his current role, he serves as an electrical subject matter expert in the development of products and services that support NFPA documents and stakeholders. Hannahs is a third-generation electrician, holding licenses as a master electrician, contractor, inspector, and plan reviewer in the state of Michigan. Having held roles as an installer, owner, and executive previously, he has also provided electrical apprenticeship instruction for over 15 years. Hannahs was twice appointed to the State of Michigan’s Electrical Administrative Board by former Governor Rick Snyder, and he received United States Special Congressional Recognition for founding the B.O.P. (Building Opportunities for People) Program, which teaches construction skills to homeless and underprivileged individuals.

Share on Socials!

NFPA 70B: A Monumental Shift in Electrical Safety

Best Practices for Electrical Safety Programs

Why De-Energized Maintenance (and not IR) Gives You the Most Bang for Your Buck

Leaders in Electrical Safety

• Aramark

• Bowtie Engineering

• Enespro

• Ericson

• I-Gard Corporation

• IRISS

• KERMEL, INC.

• Lakeland Industries

• MELTRIC Corporation

• National Safety Apparel

• National Technology Transfer

• Oberon

• Saf-T-Gard

• SEAM Group

Subscribe!

Sign up to receive our industry publications for FREE!